Not finished yet…

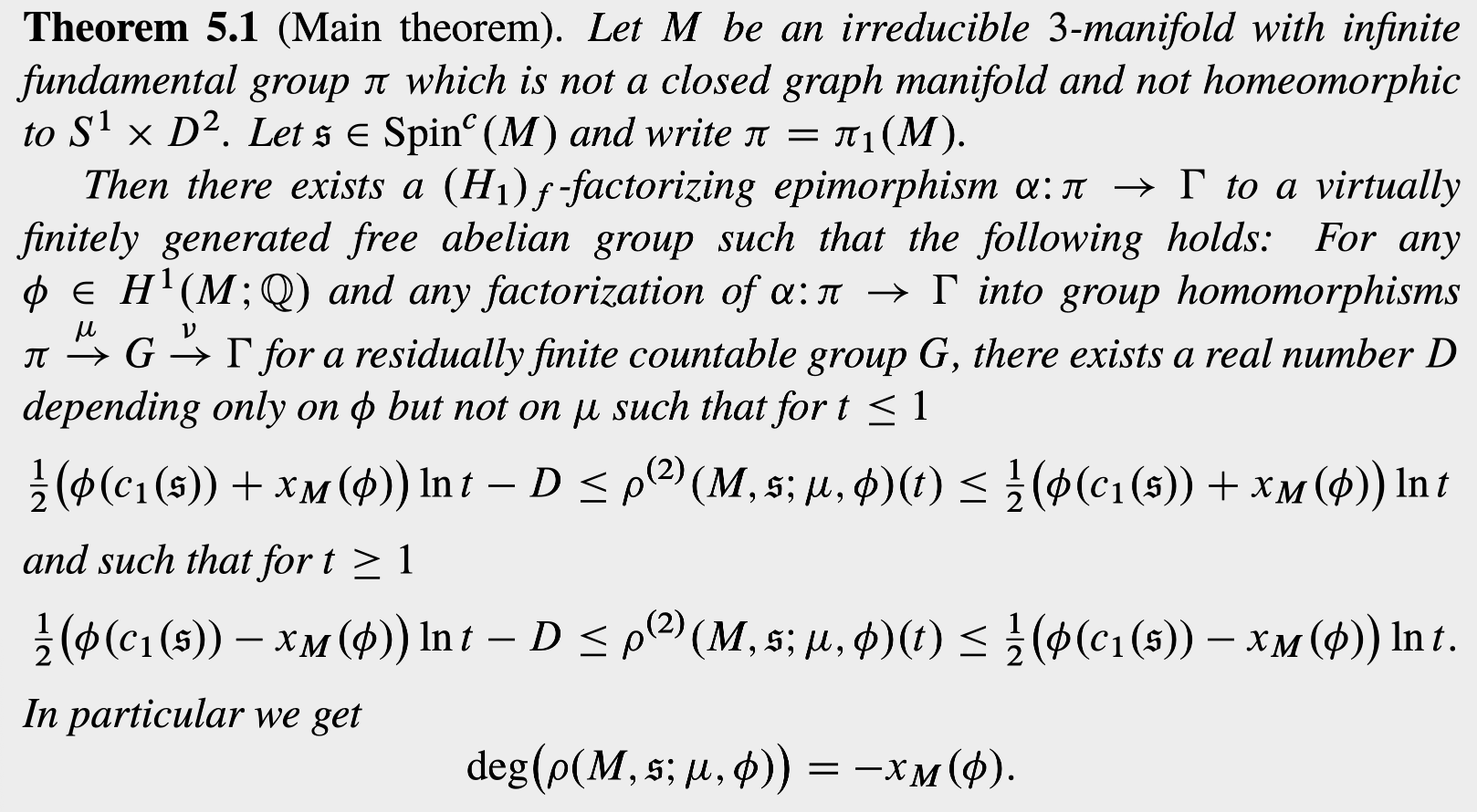

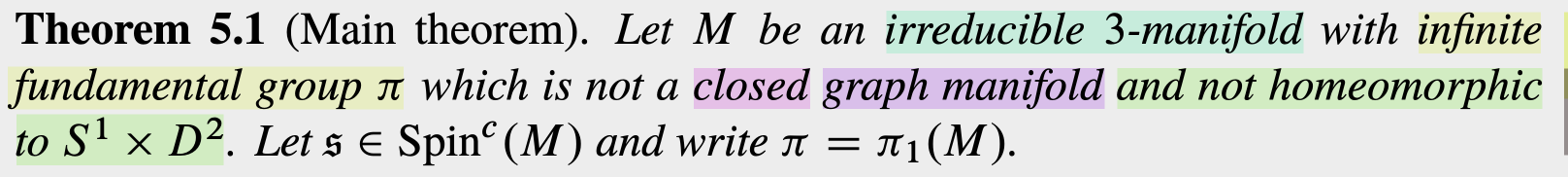

My masters thesis is about the following statement from the 2019 paper “The \(L^2\)-torsion function and the Thurston norm of 3-manifolds” by Friedl and Lück:

Let us first unravel what this theorem really means step by step.

The manifold \(M\)

Lets inspect the first requirements:

Further up in the text the authors specify that all manifolds are compact, connected, and oriented, unless otherwise specified. So \(M\) must be as well.

We will also assume like Friedl and Lück that all 3-manifolds are compact, connected, and oriented, unless otherwise specified.

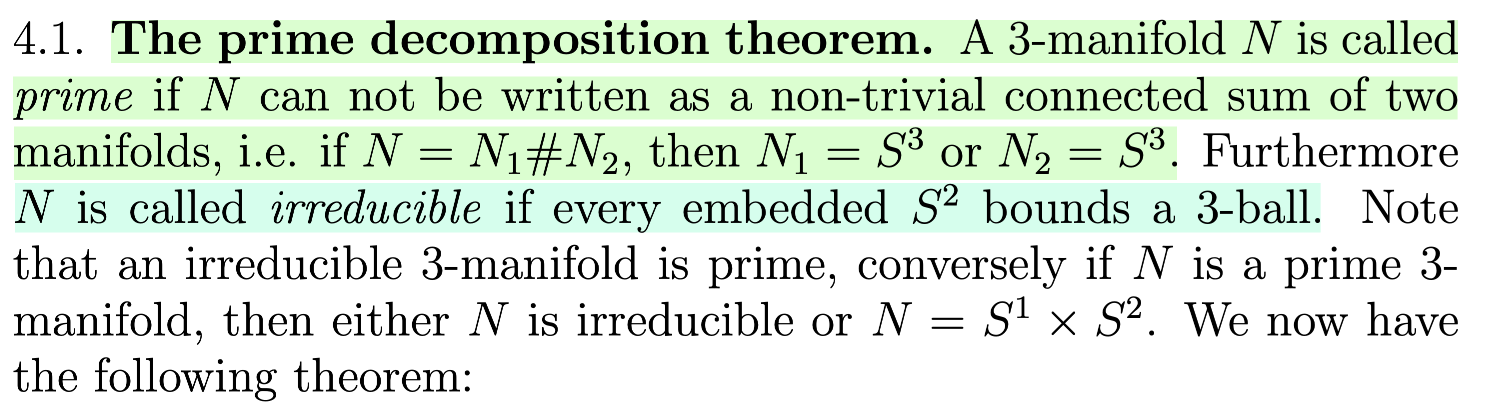

Irreducible

We have a definition by Friedl in “AN INTRODUCTION TO 3-MANIFOLDS”

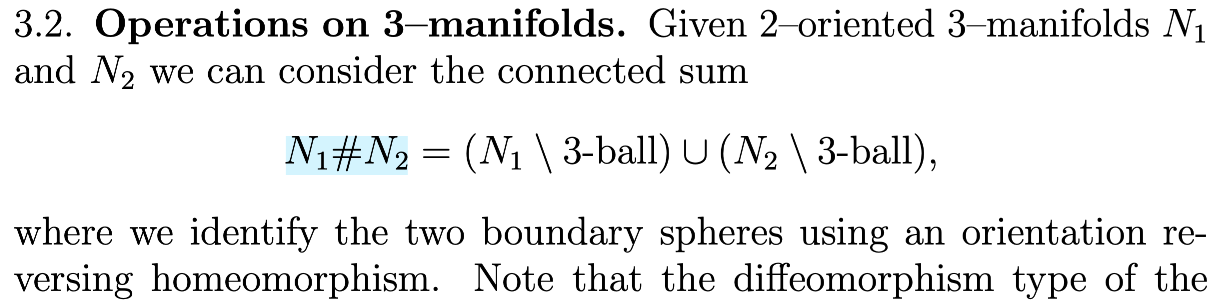

For this we need to define the connected sum of two 3-manifolds:

In the case of 2-manifolds, this video visualizes it well:

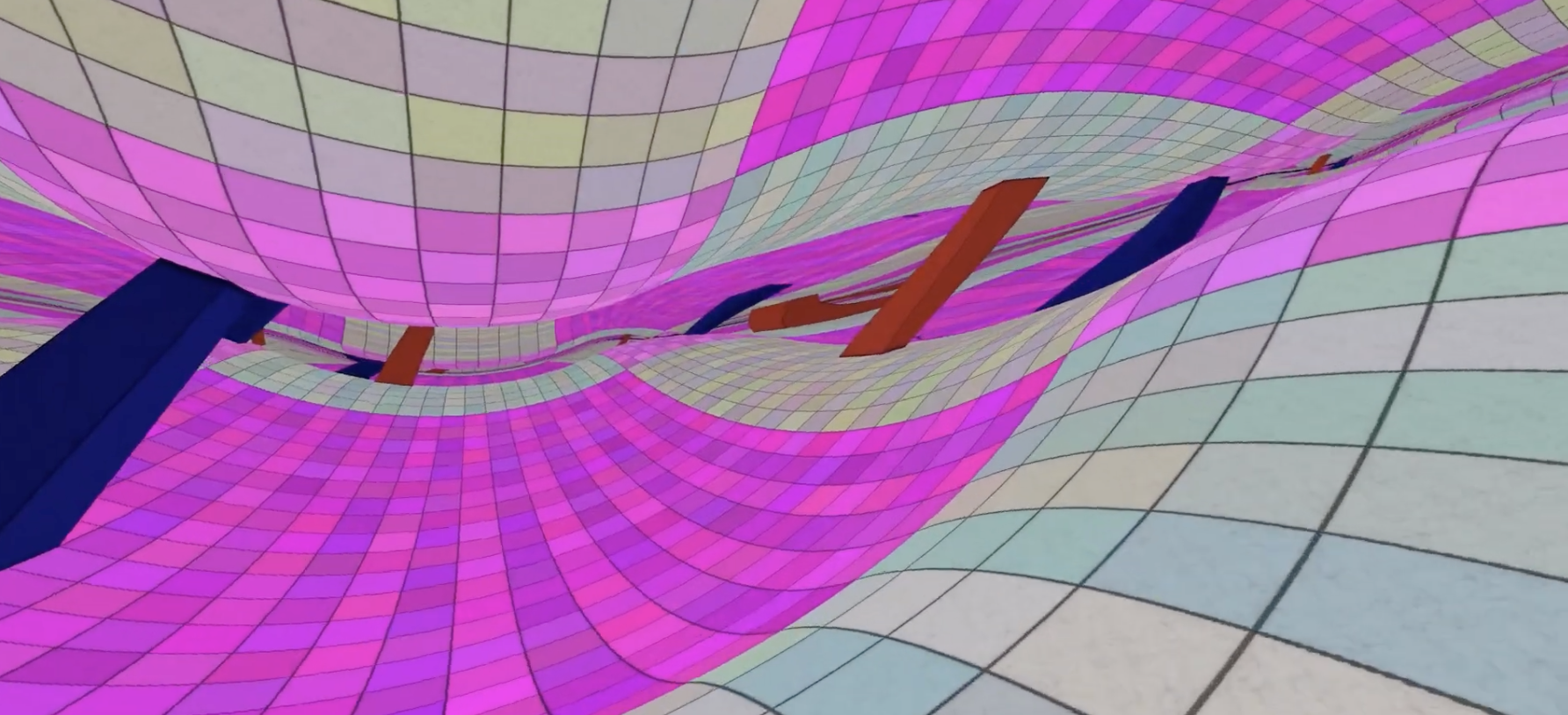

and for 3-manifolds (specifically \(\mathbb{R}^3 \# \mathbb{R}^3\)) this can be seen as adding a wormhole between two copies of \(\mathbb{R}^3\):

Or another way to look at this connected sum is by “cutting out” some region in \(N_1\) and “pasting” \(N_2\) in there. We may even do this an infinite amount of time in a checkerboard pattern, as shown here:

In this video the relevant section shows this infinite tiling where 3-manifolds with different geometries are glued together in an alternating pattern:

So being irreducible means either of the following equivalent conditions hold: - every embedded \(S^2\) of \(M\) bounds a \(D^3\). - \(M\) is prime (\(M = N_1\# N_2 \implies N_1 = S^3 \text{ or } N_2 = S^3\)) or \(M = S^1 \times S^2\).

Infinite fundamental group

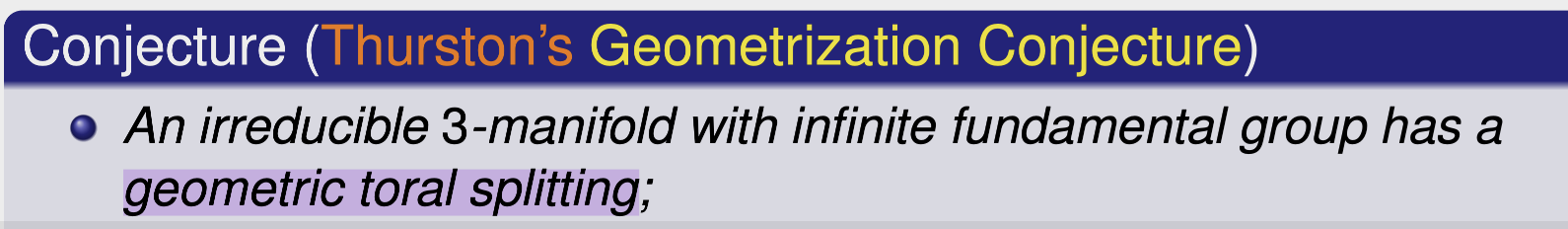

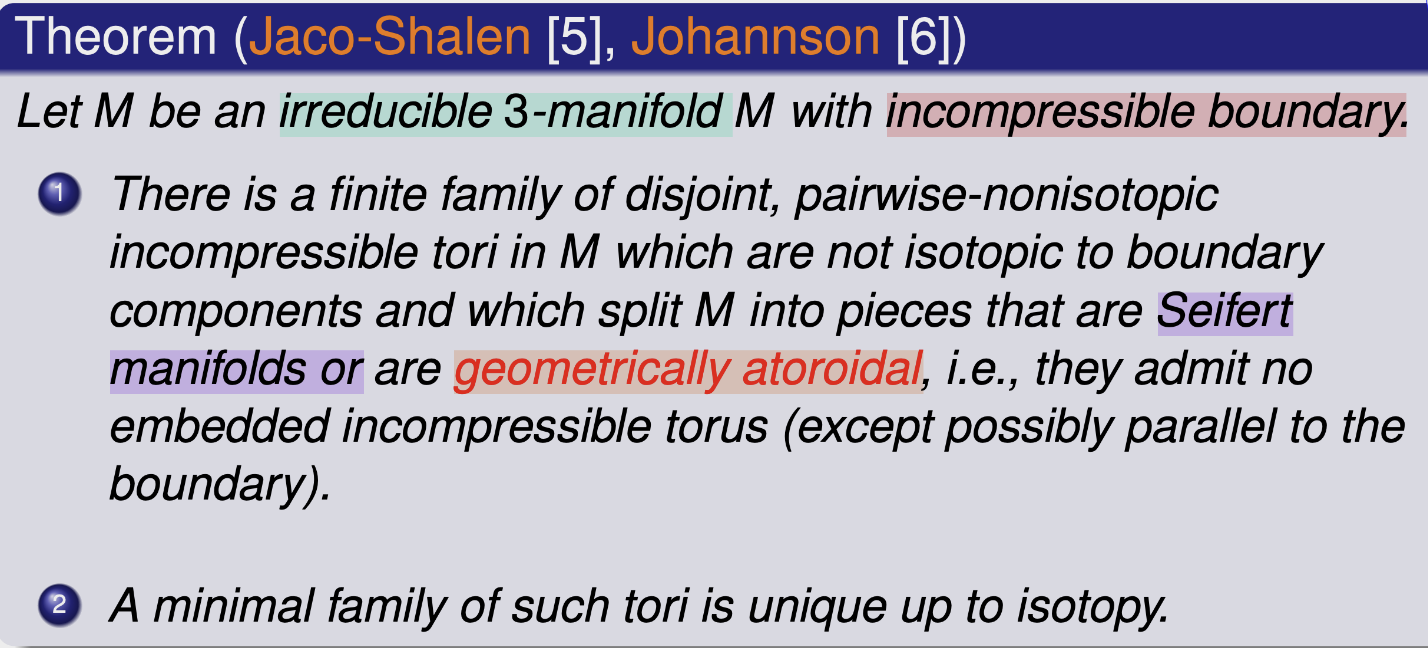

Aka. \(\|\pi_1(M)\| = \infty\). We use this to apply the famous Thurston geometrization theorem (these slides are from Lücks “Introduction to 3-manifolds” talk in Bonn):

What is a “geometric toral splitting” you may ask?

Here is a tool to play around this this definition (it only includes tori, and no framed knots!):

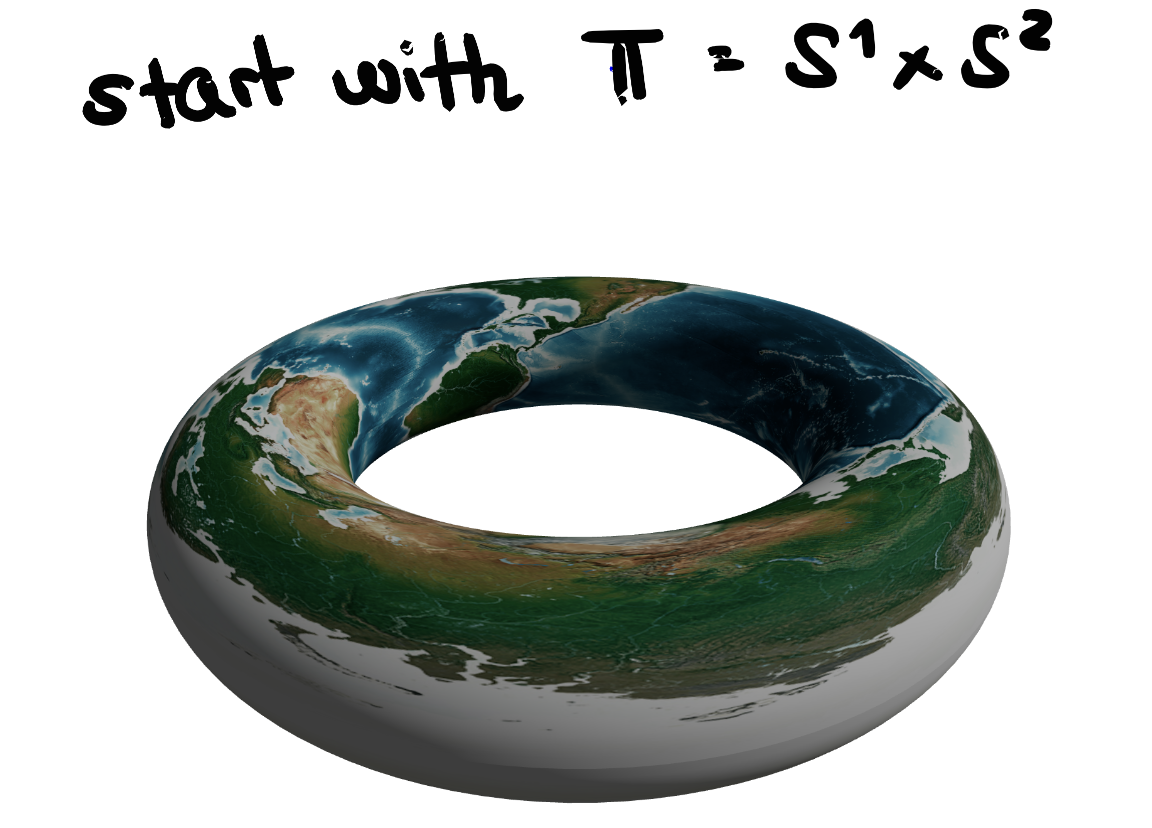

The individual tori above are have a globe texture each:

A surface \(\iota : S \hookrightarrow M\) is incompressible, if it induces an injection on the fundamental groups, i.e. \(\pi_1(\iota) : \pi_1(S) \hookrightarrow \pi_1(M)\) is injective.

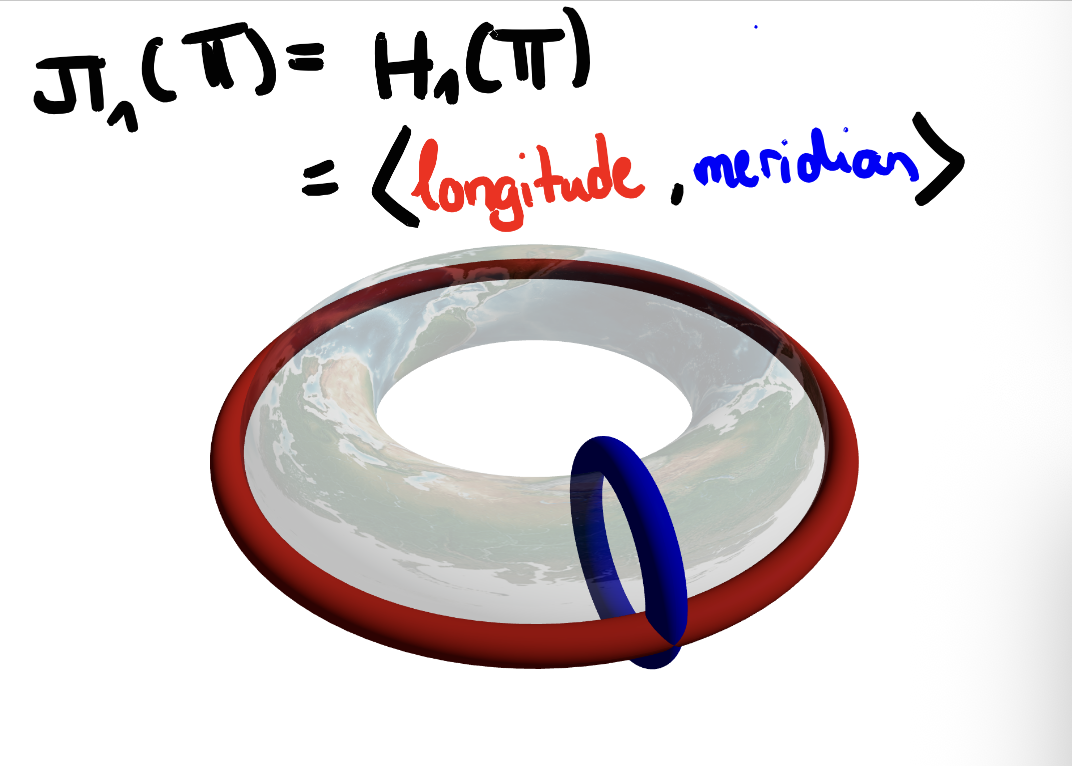

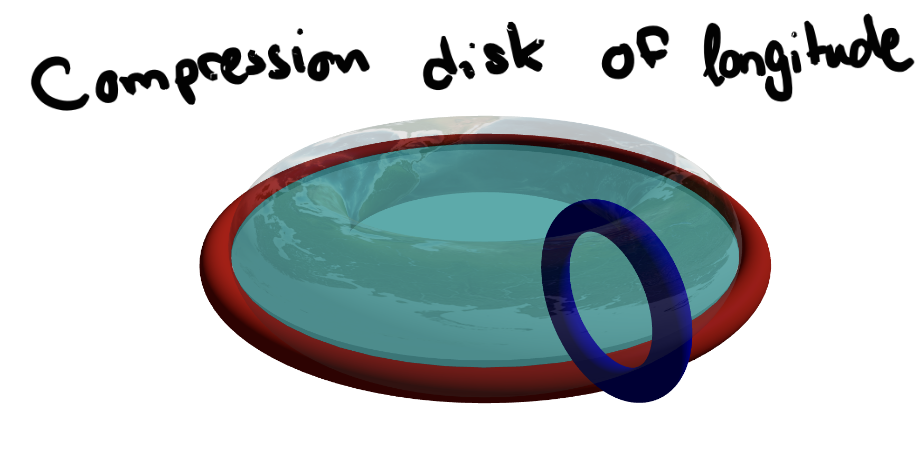

What could cause \(\pi_1(\iota)\) to fail at being injective? By the Hurewicz theorem, the first homology group \(H_1(S)\) is the abelianization of \(\pi_1(S)\), but for \(S\) a torus, \(\pi_1(S) = \mathbb{Z}^2\) is already abelian, so \(H_1(S) = \pi_1(S)\). \(H_1(S)\) is generated by the longitude and the meridian of the torus, so if either of those is sent to zero by \(\pi_1\), then \(\pi_1(\iota)\) cannot be injective.

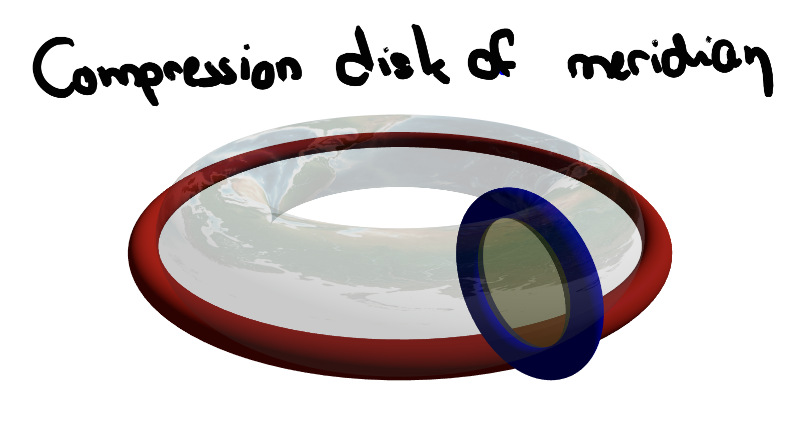

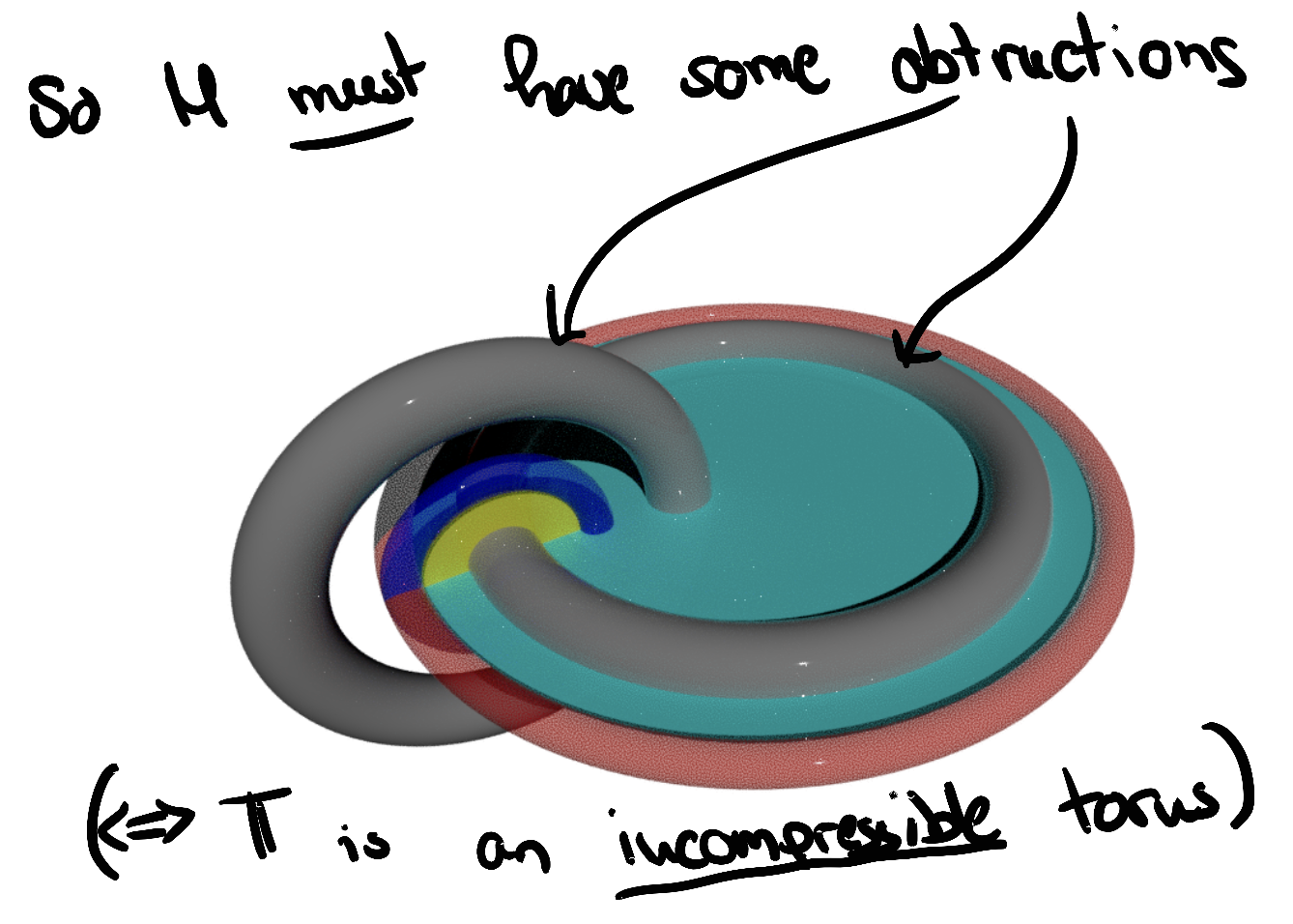

Remember, that either of these loops will dissapear, if the ambient manifold \(M\) contains a disk (a compressing disk), which will allow these loops to be contracted to a point:

Well, these disks cannot exist, iff \(M\) contains some obstruction to prevent such complressing disks.

This also explains what it means for \(M\) to have “incompressible boundary”: \[ \pi_1(\partial M) \hookrightarrow \pi_1(M) \text{ is injective} \]

This covers “disjoint” and “incompressible”. What does it mean for a torus to not be isotopic to a boundary component? Lets consider an example: