Given a group \(G\), the commutator \([G,G]\) is defined as

\[ \begin{align*} \text{span} \{ [g,h] \} = \text{span} \{ ghg^{-1}h^{-1} \} \end{align*} \]

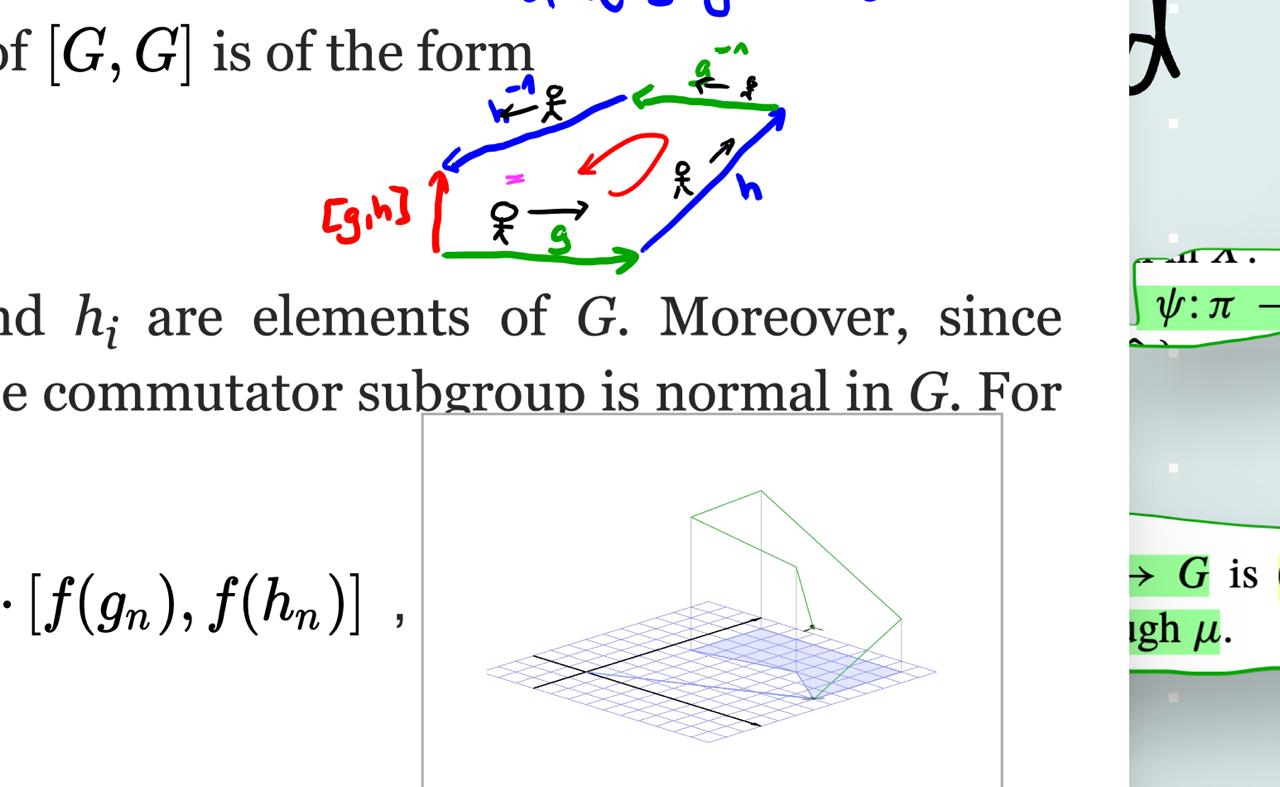

Let us consider \(G\) as a “space” of a videogame, in which a player may move around in. The players position is then given by an element \(p \in G\). Assume that \(G\) is finitely generated by a set of generators \(S\). Then the player can move around in \(G\) by applying the generators to their position. For example, if \(s \in S\) is a generator, then the player can move from position \(p\) to position \(ps\). I have visualized this idea previously on my Instagram account: https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/17907335377797682/

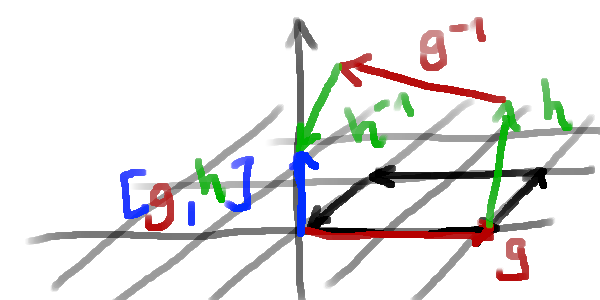

It might so happen that when a player moves in a circle, that he does not end up at the place location at which he started:

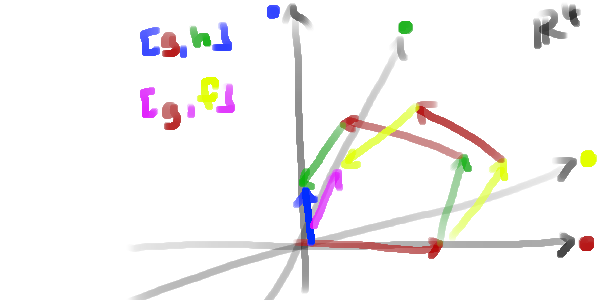

The commutator subgroup detects all these displacements (here shown in blue):

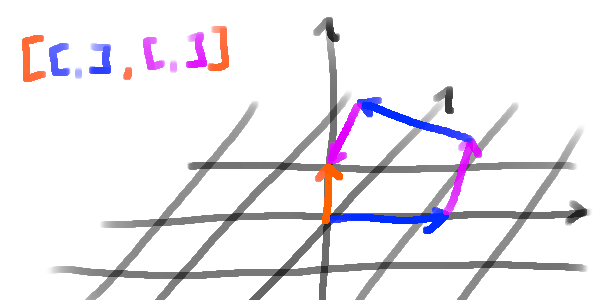

We can iterate this process and look at the commutator of the commutator, and so on. This gives us the derived series of a group:

\[ \begin{align*} G^{(0)} &= G \\ G^{(1)} &= [G,G] \\ G^{(2)} &= [G^{(1)}, G^{(1)}] \ &\vdots \end{align*} \]

Which we can also visualize as follows:

I am unsure if this is actually deeply connected or not, but I came across this idea while watching this YouTube video by Zeno Rogue: